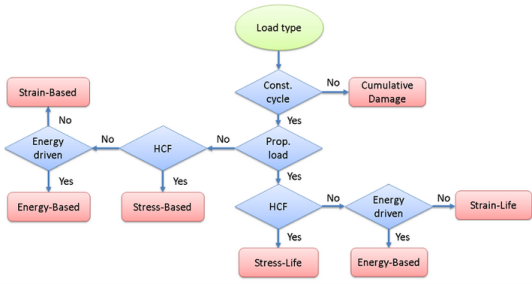

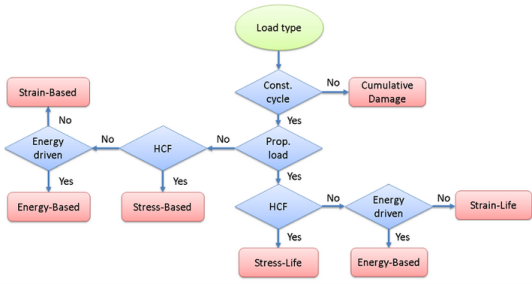

In the Fatigue Module, the Stress-Life Models and

Strain-Life Models models can evaluate fatigue at proportional loading. These models are based on a fatigue-life curve, which provides a direct relation between the fatigue life and the applied stress or strain amplitude.

One model in the Stress-Life family requires extra attention: Approximate S-N Curve Model. In the model, you specify two points on the S-N curve. The first one is the transition between the high- and low-cycle fatigue, while the second defines the endurance limit. The advantage of this model is that it does not require any substantial knowledge of the fatigue material data, since the two required points can be related to the ultimate tensile strength. Although it is a rough approximation, it is a good starting point when you lack material data.

The Strain-Based Fatigue Models are suitable for fatigue prediction at low-cycle fatigue, while the

Stress-Based Fatigue Models are frequently used to predict high-cycle fatigue. Most of the fatigue models predict the number of cycles until failure. The

Stress-Based Fatigue Models predict a fatigue usage factor, which is the fraction between the applied stress and the stress limit. This indicates to the user whether the stress limit has been exceeded and failure is expected or if the component will hold for the expected fatigue life. You can view the fatigue usage factor as the inverse of a safety factor.

Several of the Stress-Based and the Strain-Based models incorporate normal stress fatigue sensitivity. The Dang Van model from the Stress-Based family takes into account the compressive stress instead and is therefore suitable for contact fatigue analysis.

The Energy-Based Fatigue Models are frequently used in nonlinear materials in the low-cycle fatigue regime. Since the energy can be calculated in different ways, the

Energy-Based Fatigue Models can be used in both proportionally and non-proportionally loaded applications.