You are viewing the documentation for an older COMSOL version. The latest version is

available here.

|

|

In the literature, the terms viscoplasticity and creep are often used interchangeably to refer to the class of problems related to rate-dependent plasticity. A distinction is sometimes made so that creep refers to models without a yield surface.

|

|

•

|

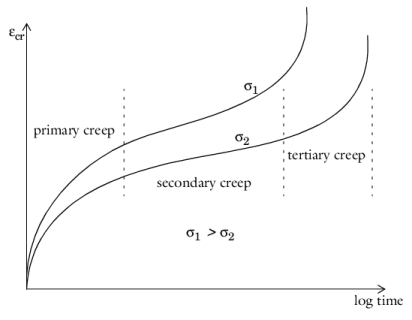

In the initial primary creep regime (also called transient creep) the creep strain rate decreases with time to a minimum steady-state value.

|

|

•

|

In the secondary creep regime the creep strain rate is almost constant. This is also called steady-state creep.

|

|

•

|

In the tertiary creep regime the creep strain increases with time until a failure occurs.

|

In most cases, Fcr1 and

Fcr3 depend on stress, temperature, and time, while secondary creep,

Fcr2, depends only on stress level and temperature. Normally, secondary creep is the dominant process. Tertiary creep is seldom important because it only accounts for a small fraction of the total lifetime of a structure or mechanical component.

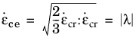

where λcr is the creep multiplier,

Qcr is the creep potential, and

σ is the stress tensor. The creep multiplier is an explicit function of stress

σ, temperature

T, time

t, and the equivalent creep strain

εce, and can be given on a general format as

where the generic functions f,

g, and

h that define the creep rate and can be combined to construct different types of creep models. The hardening rule,

h(εce,

t), defines the relationship between the creep strain tensor

εcr and the equivalent creep strain

εce. The equivalent stress

σe is a scalar representation of the Cauchy stress tensor, and given associative creep flow, it also defines the creep potential so that

The creep rate function f is typically a function of the equivalent stress

σe or any other scalar measure of the current stress state. In COMSOL Multiphysics, there are several built-in creep rate functions:

It is also possible to define an arbitrary expression for f so that, in principle, any creep model can be implemented. The expressions used for the built-in creep rate functions are described in the following sections.

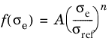

The Norton model is the most common secondary creep model, where the creep rate is assumed proportional to a power law of the equivalent stress

σe such that

(3-130)

where A is the creep rate coefficient,

n is the stress exponent,

σref is a reference stress level.

At very high stress levels the creep rate is proportional to the exponential of σe. Garofalo showed (

Ref. 8,

Ref. 9) that the power-law and exponential creep are limiting cases for the general empirical expression

This equation reduces to a power-law (the Norton model) when ασe < 0.8 and approaches exponential creep for

ασe > 1.2, where 1

/α is a reference equivalent stress level. The

Garofalo (Hyperbolic sine law) creep model implemented in COMSOL Multiphysics is given as

For metals at low stress levels and high temperatures, Nabarro and Herring (Ref. 6,

Ref. 7) independently derived an expression for the creep rate as a function of atomic diffusion, so called diffusional creep. The

Nabarro–Herring model implemented in COMSOL Multiphysics is given as

where d is the grain diameter,

Dv is the volume diffusivity through the grain interior,

b is the Burgers vector,

kB is the Boltzmann’s constant,

T is the absolute temperature.

Another model for diffusional creep is the Coble creep model (

Ref. 6,

Ref. 7), which is closely related to Nabarro–Herring creep, but takes into account the grain boundary diffusivity through the parameter

Dgb. The

Coble creep model implemented in COMSOL Multiphysics is given as

Generally, the stress exponent n in the Weertman model takes a value between 3 and 5 when modeling dislocational creep.

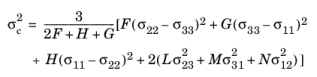

where J2 is the second invariant of the stress deviator. If creep is orthotropic, the

Hill orthotropic equivalent stress can be used, which is given by

(3-131)

where F,

G,

H,

L,

M, and

N are Hill’s coefficients that relate the anisotropy to the local coordinates. In the above equation it is assumed that an average equivalent stress can be computed from

F,

G, and

H using a von Mises like expression; this assumption leads to the first term on the right-hand-side of

Equation 3-131.

The dimensionless tensor N, which gives the direction of the creep flow, is computed from the creep potential

Qcr as

When von Mises equivalent stress is used, the potential equals Qcr = σmises, and the deviatoric tensor

Ndev is defined as done for

J2 plasticity (see

Isotropic Plasticity)

(3-132)

The same hardening rule is also used when the Hill orthotropic equivalent stress is selected.

For the Pressure equivalent stress, the flow direction is volumetric

The creep hardening function h is typically a function of time

t and the equivalent creep strain

εce. In COMSOL Multiphysics, there are two built-in hardening functions,

Strain hardening and

Time hardening, and it is also possible to specify a user defined expression. Also, it is possible to add hardening to any of the built-in creep models.

where the time hardening function is given by the power law

here, tshift is a time shift,

tref is a reference time, and

m is the hardening exponent.

Similarly, the strain hardening function is given by the power law

where εshift is the equivalent creep strain shift,

tref is a reference time, and

m is the hardening exponent.

The strain shift εshift and the time shift

tshift in the hardening functions serve two purposes:

The temperature shift function g typically depends on the absolute temperature

T. In COMSOL Multiphysics, an

Arrhenius temperature function is built-in, but it is also possible to specify a user defined expression.

The Arrhenius temperature function is given as

where Q is the activation energy (J/mol),

R is the gas constant,

T is the absolute temperature, and

Tref is a reference temperature.

Using a combination of f,

g, and

h together with the definition of the equivalent stress

σe makes it possible to construct sophisticate creep models. For example, the often used temperature-dependent isotropic Norton creep model is obtained by the following settings:

Several creep rate contributions can be added to the total creep rate to construct more elaborate models. This is done by adding one or more Additional Creep subnodes to an existing

Creep node. There are no restrictions on how to combine models; for example, a

von Mises based creep flow contribution can be combined with a

Pressure based creep flow contribution.

|

|

|

•

|

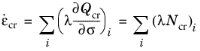

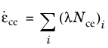

In the example Combining Creep Material Models: Application Library path Nonlinear_Structural_Materials_Module/Creep/combined_creep a Norton–Bailey model for primary creep is combined with a Norton model for secondary creep. Both creep models are temperature dependent. The resulting creep-rate equation becomes

|

|

(3-133)

(3-134)

where Ncr and

Nce are tensors that describe the direction of

εcr and

εce, respectively.

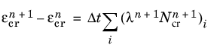

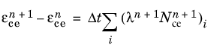

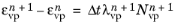

The Backward Euler method is used to discretize these equations as

(3-135)

(3-136)

where n+1 indicates that the variable is evaluated at the current time step, and

Δt is the time step. The creep strain tensor

and equivalent creep strain

at the previous time step are stored as internal state variables.

Equation 3-135 and

Equation 3-136 define a system of nonlinear equations that is solved locally at each Gauss point for

and

using Newton’s method.

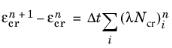

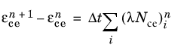

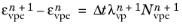

The Forward Euler method is used to discretize

Equation 3-133 and

Equation 3-134 as

(3-137)

(3-138)

such that all quantities on the right-hand-side are evaluated at the previous time step. This means that Equation 3-137 and

Equation 3-138 define an explicit update of

and

given only known quantities from the previous time step. The forward Euler method is only conditionally stable, and the time step of the global time marching scheme has to be constrained to preserve stability and accuracy of the method. In COMSOL Multiphysics the limit for a stable time step is estimated as

where εel is the elastic strain tensor. This estimate in principle restricts the creep increment to be smaller than the current state of stress, and

1/4 is a constant to make the estimate conservative. The final value is computed as the minimum value over all Gauss points in the domain where the creep feature is active.

For Domain ODEs,

Equation 3-133 and

Equation 3-134 are converted to weak-form and solved as part of the general initial-boundary value problem. The components of the creep strain tensor

εcr and the equivalent creep strain

εce are then treated as degrees-of-freedom.

The equations described in the previous sections about the different creep models differ from the forms most commonly found in the literature. The main difference lies in the introduction of normalizing reference values such as the reference stress σref and reference time t

ref. These values are in a sense superfluous and can in principle be chosen arbitrarily. The choice of reference values, however, affects the numerical values to be entered for the material data. The implementation in COMSOL Multiphysics has two advantages:

The coefficient AN has a physical dimension that depends on the value of

n, and the unit has an implicit dependence on the stress and time units. Converting the data to the format used in COMSOL Multiphysics (for example,

Equation 3-130) requires the introduction of the reference stress

σref. It is convenient here to use the implicit stress unit for which

AN is given as the reference stress. The creep rate coefficient

A will then have the same numerical value as

AN, and you do not need to do any conversions.

The physical dimension of A is, however, (time)

−1, whereas the physical dimension of

AN is (stress)

−n(time)

−1.

Another popular way of representing creep data is to supply the stress giving a certain creep rate. As an example, σc7 is the stress at which the creep strain rate is

10−7/h. Data on this form is also easy to enter: You set the reference stress

σref to the value of

σc7 and enter the creep rate coefficient

A as

1e-7[1/h].

|

•

|

σc7 = 70 MPa, and stress exponent n = 4.5.

|

|

•

|

AN = 4.98 ·10-16 with respect to units MPa and hours, and stress exponent n = 4.5.

|

Since the stress inside in the Garofalo law appears as an argument to a sinh() function, it must necessarily be dimensionless. Most commonly this is however written as

Viscoplasticity, as well as Creep, is an inelastic time-dependent deformation that occurs when the material is subjected to stress (typically much less than the yield stress). The growth of unrecoverable strains depend on the rate at which loads are applied, effect that is normally enhanced by high temperatures.

The viscoplastic strain εvp is computed by a flow rule that defines the relationship between the rate of

εvp and the current state of stress and temperature.

When an associative flow and von Mises equivalent stress σe are used, so

Qvp = σe, the rate of

εvp is coaxial to the stress deviator and the viscoplastic flow rule is written as

where Qvp is the viscoplastic potential,

σ is the stress tensor, and

Ndev = ∂Qvp / ∂σ is the flow direction.

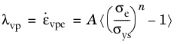

The viscoplastic multiplier λvp depicts a different expression for different viscoplastic models (Anand, Chaboche, and so on), and it is equal to the equivalent viscoplastic strain rate

Setting different measures for the equivalent stress σe (von Mises, Tresca, Hill) allows to define different viscoplastic multiplier and flow directions, see

Equivalent Stress, Creep Flow and Hardening Rule for details.

Anand viscoplasticity (Ref. 9) is a deviatoric viscoplastic model suitable for isotropic viscoplastic deformations. As for the models described in

Creep, the Anand model has no yield surface.

The rate of εvp is determined by the viscoplastic multiplier

λvp which is a function of stress

σ and temperature

T, and it is given by

here, A is the viscoplastic rate coefficient,

Q is the activation energy (J/mol),

ξ is the stress multiplier,

m is the stress sensitivity, and

R is the gas constant.

The deformation resistance, sa (SI unit: Pa), controls the hardening behavior of the Anand model. In COMSOL Multiphysics it is derived for the normalized

resistance factor, sf, and the

deformation resistance saturation coefficient,

ssat, such that

sa =

ssat sf. The resistance factor

sf is a dimensionless internal variable that is computed by the evolution equation

with the initial condition sf(0) = sinit /

ssat. The evolution of the resistance factor

sf is controlled by the dimensionless hardening function

were h0 (SI unit: Pa) represents a constant rate of

athermal hardening in the curve stress versus strain (

Ref. 9). The use of the sign function and the absolute value in the hardening function permits the modeling of either strain hardening or strain softening, depending on whether

sf is greater or smaller than the saturation value

sf*.

The saturation value sf* is calculated from the expression

where n is the

deformation resistance sensitivity exponent.

Anand–Narayan model (Ref. 10) is suitable for modeling the viscoplastic deformation of lithium.

where A is the viscoplastic rate coefficient,

Q is the activation energy (J/mol),

ξ is the stress multiplier,

m is the stress sensitivity, and

R is the gas constant.

The deformation resistance, sa (SI unit: Pa), is computed with an extra dependent variable as done for

Anand Model.

for

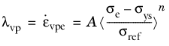

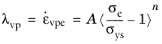

for

Here, A is the viscoplastic rate coefficient (SI unit: 1/s),

n is the stress exponent (dimensionless), and

σref is a reference stress level (SI unit: Pa).

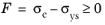

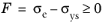

The Macaulay brackets < • > are applied on the yield function, which is defined as done for plasticity

The equivalent stress σe is either the von Mises, Tresca, or Hill orthotropic stress, or a user defined expression; and

σys is the yield stress (which may include an

Numerical Solution of the Elastoplastic Conditions model). The stress tensor used in the equivalent stress

σe is shifted by what is usually called the

back stress,

σback when

Kinematic Hardening is included.

The deviatoric tensor Ndev is computed from the viscoplastic potential

Qvp

When von Mises equivalent stress is used, the associated flow rule reads Qvp = F, and the deviatoric tensor

Ndev is defined as done for deviatoric creep.

for

for

As described for Chaboche Model, the equivalent stress

σe can be either von Mises (default), Tresca, Hill orthotropic stress, or a user defined expression. The flow direction

Ndev = ∂Qvp / ∂σ is computed from the viscoplastic potential

Qvp, which can be associated or nonassociated.

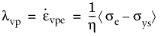

Bingham model is equivalent to Chaboche Model when setting the exponent

n = 1, and denoting the viscosity as the quotient

η = σref/

A. The equivalent viscoplastic strain rate (viscoplastic multiplier) is given by

for

for

As described for Chaboche Model, the equivalent stress

σe can be either von Mises (default), Tresca, Hill orthotropic stress, or a user defined expression. The flow direction

Ndev = ∂Qvp / ∂σ is computed from the viscoplastic potential

Qvp, which can be associated or nonassociated.

for

for

As described for Chaboche Model, the equivalent stress

σe can be either von Mises (default), Tresca, Hill orthotropic stress, or a user defined expression. The flow direction

Ndev = ∂Qvp / ∂σ is computed from the viscoplastic potential

Qvp, which can be associated or nonassociated.

for

for

The conditional evaluation F ≥ 0 is handled automatically.

By default, an associative flow and von Mises equivalent stress σe are used, so

Qvp = F, the rate of

εvp is coaxial to the stress deviator, and the viscoplastic flow rule is written as

The temperature function g typically depends on the absolute temperature

T. In COMSOL Multiphysics, an

Arrhenius temperature function is built-in, but it is also possible to specify a user defined expression.

The Arrhenius temperature function is given as

where Q is the activation energy (J/mol),

R is the gas constant,

T is the absolute temperature, and

Tref is a reference temperature.

The rate equations given by the viscoplastic flow rule and evolution equations for the two internal variables are integrated in time to compute the value of the viscoplastic strain tensor εvp, the equivalent creep strain

εvpe, and other possible internal variables (for instance, the resistance factor

sf in Anand model) at each time step. This can be done using any of the following methods:

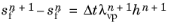

The Backward Euler method is used to discretize these equations as

(3-139)

(3-140)

where Nvp and

Nvpe are tensors that describe the direction of

εvp and

εvpe, respectively,

n+1 indicates that the variable is evaluated at the current time step, and

Δt is the time step.

For Anand Model an extra equation is solved for the

resistance factor, sf,

(3-141)

For Domain ODEs, the evolution equations of the viscoplastic model are converted to weak-form and solved as part of the general initial-boundary value problem. The components of

εvp,

εvpe, and

sf are then treated as degrees of freedom.

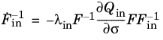

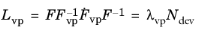

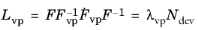

When the Large strains formulation is selected in the

Creep or

Viscoplasticity nodes, a

Multiplicative Decomposition of deformation gradients is used

here, F is the deformation gradient,

Fel is the elastic deformation, and

Fin is inelastic deformation due to creep or viscoplasticity.

(3-142)

where λin is the equivalent creep or viscoplastic strain rate, and

Qin is the creep or viscoplastic potential. For creep and viscoplasticity in metals (so-called

J2 plasticity) the viscoplastic potential depends on the deviatoric stress,

Qin = Qin(J2 (σ)), and the flow direction is deviatoric,

Ndev = ∂Qin / ∂σ.

For large strains, Equation 3-142 is numerically solved with the so-called

exponential mapping technique, as described in

Numerical Solution of the Elastoplastic Conditions, and the elastic deformation gradient then obtained from

The Bergstrom–Boyce model (Ref. 35–

36) is a viscoplastic material that successfully capture such phenomena, and it is suitable for modeling rubbers and elastomers.

The stiffness in the spring is defined by the energy factor βv. This factor multiplies the isochoric strain energy density defined in the main hyperelastic branch, in a similar way as done for

Large Strain Viscoelasticity. For instance, if the main branch is defined by an

Arruda–Boyce hyperelastic material with a shear modulus

μ0, then the shear modulus in the spring is

μ1 = βvμ0.

here, F is the deformation gradient in the hyperelastic branch,

Fel is the elastic deformation in the spring, and

Fvp is inelastic deformation in the dashpot.

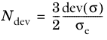

The viscoplastic velocity gradient, Lvp, is energy conjugate to the stress tensor

σ in the branch. For volume-preserving viscoplasticity, it is defined as

with

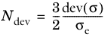

with

for

for

here, A is the viscoplastic rate coefficient,

σe is the von Mises stress in the network,

σco is a cutoff stress,

σres is the flow resistance, and

n is the stress exponent.

The strain hardening function h(λvpe) is defined by the power-law

Here, c is the strain hardening exponent and

ξ is a small numerical constant. The equivalent viscoplastic stretch

λvpe is computed from the viscoplastic deformation

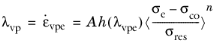

The Bergstrom–Bischoff model, also known as the three network model (

Ref. 35,

Ref. 37) is suitable for modeling elastomers and thermoplastics. The rheology is similar to the Bergstrom–Boyce model, but it adds two parallel branches instead of one.

The stiffness in the spring in the first branch is defined by the energy factor βv1. This factor multiplies the isochoric strain energy density defined in the main hyperelastic branch, in a similar way as done for

Bergstrom–Boyce Model. For instance, if the main branch is defined by an

Arruda–Boyce hyperelastic material with a shear modulus

μ0, then the stiffness in the spring is

μ1 = βv1μ0.

here, A is the viscoplastic rate coefficient,

σe,1 is the von Mises stress in the branch,

σres,1 is the flow resistance,

a1 is a material parameter to control the influence of the hydrostatic stress, and

n1 is the stress exponent.

The energy factor in the second branch βv2 is computed after solving the rate equation

Here, βv2 is the final energy factor after saturation. The energy factor is initialized to a value equal to

βv2 = βvi. The energy factor

βv2 then multiplies the isochoric strain energy density defined in the main hyperelastic branch to define the stiffness of the spring in the second branch, in a similar way as done in the first branch.

here, σe,2 is the von Mises stress in the branch,

σres,2 is the flow resistance,

a2 is a material parameter to control the influence of the hydrostatic stress, and

n2 is the stress exponent.

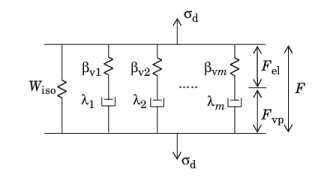

The Parallel Network model (Ref. 35,

Ref. 37) can be seen as a generalized version of the

Bergstrom–Boyce Model, where several viscoplastic branches can be added in parallel to the main hyperelastic branch.

For example, it is possible to combine a Neo-Hookean material in the main hyperelastic branch with two parallel spring-dashpot branches characterized by an

Arruda–Boyce model.

Several networks can be added to build more elaborate viscoplasticity models, and the energy factors βvi are used to differentiate the response of the additional stiffnesses. This is done by adding one or more

Additional Network subnodes to an existing

Polymer Viscoplasticity node. The rheological representation of this model can be seen in

Figure 3-29.

with

with

The temperature function g(

T) depends on the absolute temperature

T, and it acts as a multiplier for the viscoplastic rate.

The Arrhenius temperature function is given as

where Q is the activation energy (J/mol),

R is the gas constant,

T is the absolute temperature, and

Tref is a reference temperature.

The Power law temperature function is given as

where T is the absolute temperature,

Tref is a reference temperature, and

m is the temperature exponent.

|

|

When the Calculate dissipated energy check box is selected, the dissipation rate density due to creep is available under the variable solid.Wcdr and the dissipation rate density due to viscoplasticity is available under the variable solid.Wvpdr. The dissipated energy density due to creep is available under the variable solid.Wc and due to viscoplasticity under the variable solid.Wvp. Here solid denotes the name of the physics interface node.

|