|

|

1·10-7 psi·s

|

||

|

0.43·106 psi

|

||

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

Click Add.

|

|

4

|

Click

|

|

5

|

|

6

|

Click

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

Click Browse.

|

|

4

|

Browse to the model’s Application Libraries folder and double-click the file multilateral_well.mphbin.

|

|

5

|

Click Import.

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

1

|

In the Model Builder window, under Component 1 (comp1) right-click Materials and choose Blank Material.

|

|

2

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

1

|

In the Model Builder window, under Component 1 (comp1)>Darcy’s Law (dl) click Poroelastic Storage 1.

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

1

|

|

1

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

1

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

1

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

1

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

1

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

5

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

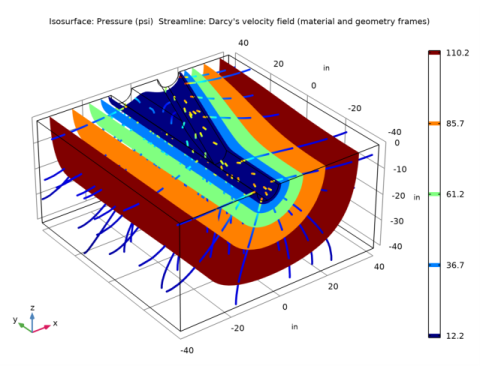

In the Settings window for 3D Plot Group, type Fluid Pressure and Velocities in the Label text field.

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

In the Settings window for Streamline, click Replace Expression in the upper-right corner of the Expression section. From the menu, choose Component 1 (comp1)>Darcy’s Law>Velocity and pressure>dl.u,...,dl.w - Darcy’s velocity field (material and geometry frames).

|

|

3

|

Locate the Streamline Positioning section. From the Positioning list, choose Starting-point controlled.

|

|

4

|

|

5

|

Locate the Coloring and Style section. Find the Line style subsection. From the Type list, choose Tube.

|

|

6

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

5

|

|

6

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

5

|

|

6

|

Click

|

|

7

|

|

8

|

|

9

|

|

10

|

Click Replace.

|

|

11

|

|

12

|

|

13

|