Magnetostriction has a quantum-mechanical origin. The magneto-mechanical coupling takes place at the atomic level due to spin-orbit coupling. From a system level, the material can be assumed to consist of a number of tiny ellipsoidal magnets which rotate due to the torque produced by the externally applied magnetic field. The rotation of these elemental magnets produces a dimensional change leading to free strain in the material.

It is possible to express the relation between the stress S, strain

ε, magnetic field

H, and magnetic flux density

B in either a

stress-magnetization form or

strain-magnetization form:

where μ0 is the magnetic permeability of free space,

cH and

sH are respectively the stiffness and compliance matrices measured at constant magnetic field, and

μrS and

μrT are the relative magnetic permeabilities measured at constant strain and constant stress, respectively. The matrices

dHT and

eHS are called piezomagnetic coupling matrices.

You find all the necessary material data inputs within the Magnetostrictive Material node under the Solid Mechanics interface, which are added automatically when you add a predefined Magnetostriction multiphysics interface. Such a node can be also added manually under any Solid Mechanics interface similar to all other material model features. The

Magnetostrictive Material uses Voigt notation for the anisotropic material data. More details about the data ordering can be found in

Orthotropic and Anisotropic Materials section.

All domains have magnetization of the same magnitude |M|

= Ms, but the magnetization can have different orientations characterized by the corresponding direction vector

m = M/Ms for each domain. The applied magnetic field changes the domain orientation.

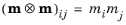

where  . Note that the magnetostrictive strain is represented by a deviatoric tensor, that is, tr(εme) = 0

. Note that the magnetostrictive strain is represented by a deviatoric tensor, that is, tr(εme) = 0. This is because the deformation is related to the magnetic domain rotation, and such process should not change the material volume.

The strain field is deviatoric, and Equation 3-56 exhibits the same properties as

Equation 3-54 at saturation, that is, when |

M|

→ Ms.

Equation 3-55 is replaced by

Note that the strain vanishes when |M|

→ 0, which makes the model applicable in the whole range from full demagnetization to saturation.

For isotropic materials, the stiffness matrix cH can be represented in terms of two parameters, for example, using the Young’s modulus and Poisson’s ration. Cubic materials possess only three independent components:

c11,

c12, and

c44.

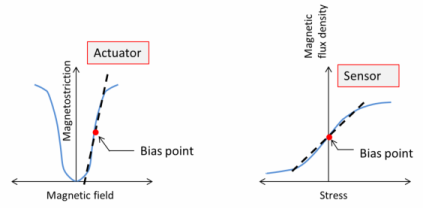

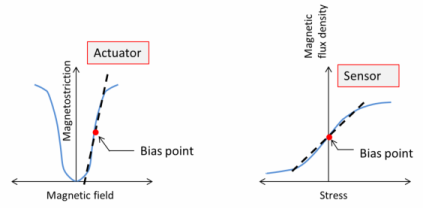

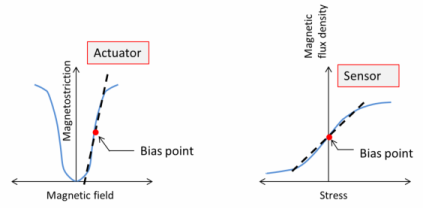

Using Equation 3-57, one can derive a linear response around a given bias state characterized by a premagnetization vector

M0. Thus,

with χm being the magnetic susceptibility in the initial linear region.

Other possible choices of the L function are a hyperbolic tangent

where H is the applied magnetic field. The second term in

Equation 3-58 represents the mechanical stress contribution to the effective magnetic field, and thus to the material magnetization, which is called the

Villari effect. The deviatoric stress tensor is related to the strain as

COMSOL Multiphysics solves for the magnetic vector potential A whose curl yields the vector

B-field. The

H-field is then obtained as a function of the

B-field and magnetization.