When adhesion is active, it is possible to break the bond between the source and destination boundaries by adding a Decohesion subnode to

Contact. Decohesion modifies the stress vector

f defined by

Adhesion, but does not explicitly add any new contribution to the virtual work on the destination boundary. It thus requires an active

Adhesion node.

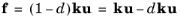

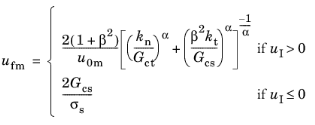

(3-227)

where d is the damage variable. During crack opening (or shearing), the damage variable grows, resulting in a softening behavior of the interface until it eventually breaks when

d = 1, see

Figure 3-43. If the interface is unloaded, the material follows the linear secant stiffness as defined by the current state of damage. No permanent deformations remain at complete unloading.

The Decohesion subnode implements the second term on the right-hand side of Equation 3-227, while the first term is implemented in

Adhesion. Notice that in the normal direction, damage only applies to separation of the boundaries, hence the normal contact is unaffected by decohesion.

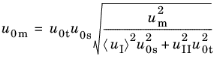

In the displacement-based damage models, the damage variable d is defined using a damage evolution function written in terms of a displacement quantity. Since, in general, the fracture is a combination of mode I and mode II fracture, the model introduces a mixed mode displacement

um as the norm of the displacement jump vector.

where  is and internal degree of freedom that takes the value of um,max

is and internal degree of freedom that takes the value of um,max at the previous converged solution. The damage variable is then defined as a function of

um,max of the form

where F–1 is called the

damage evolution function and

u0m defines the onset of damage. Conceptually, the damage evolution function is the inverse of the softening branch of the traction–separation law

F. Four different definitions of the damage evolution function

F−1 are available in the

Traction–separation law list.

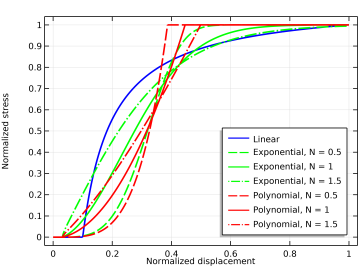

The Linear option specifies a damage evolution function that gives a bilinear traction–separation law as seen in

Figure 3-43. It is defined as

where u0m and

ufm define the

mixed mode initiation of damage and point of complete fracture, respectively. For the initiation of damage, a linear mixed mode criterion gives

(3-228)

where uI and

uII are the mode I and mode II displacements, respectively. These are obtained from the displacement jump vector

u. The constants

u0t and

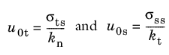

u0s are calculated as

(3-229)

where σts is the tensile strength and

σss is the shear strength of the adhesive layer. The

normal stiffness kn and the equivalent

tangential stiffness kt are obtained from the adhesive stiffness vector

k. The mixed mode failure displacement

ufm depends on the selected

Mixed mode criterion.

The Power Law criterion is defined as

the Generalized Power Law criterion is defined as

and the Benzeggagh–Kenane criterion is defined as

where Gct,

Gcs, and

Gcm are the tensile, shear, and total energy release rates, respectively. The parameter

α is called the

mode mixity exponent. For the generalized power law criterion, the tensile and shear energy release rates have different mode mixity exponents,

αt and

αs respectively.

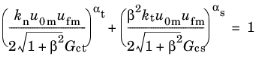

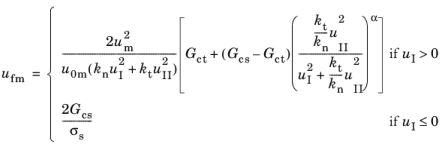

From these relations, the mixed mode failure displacement ufm is calculated. For the power law criterion it reads

(3-230)

where the mode mixity ratio reads

β = uII/uI.

(3-231)

(3-232)

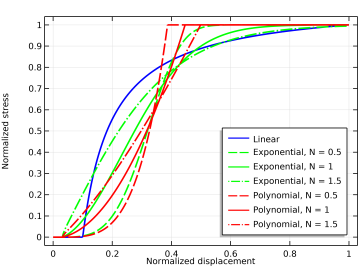

The Exponential option specifies a damage evolution function that gives a traction–separation law which is linear up to the interface strength, and thereafter softens with an exponential curve that asymptotically reaches zero as shown in

Figure 3-43,

The Polynomial option specifies a damage evolution function that gives a linear traction–separation law up to the interface strength, it thereafter softens with a cubic polynomial curve as shown in

Figure 3-43,

The Multilinear option specifies a damage evolution function that gives a traction–separation law that is linear up to the interface strength. Thereafter a region of constant stress is introduced before the interface softens linearly as seen in

Figure 3-43.

The variable upm defines the end of the region of constant stress and introduces the

shape factor λ. The shape factor defines the ratio between the constant stress part of

Gct and the total “inelastic” part of

Gct:

where the index i indicates either tension or shear.

For the multilinear option, the mixed mode criterion is always linear (α = 1). Hence the mixed mode stress plateau displacement,

upm, and the failure displacement,

ufm, are given as

From the stored energy ψ(

u,

d), the stress vector

f and damage energy release rate

Ydm are obtained as

where  is an internal variable that takes the value of Ydm,max

is an internal variable that takes the value of Ydm,max at the previous converged solution. The energy dissipated during the decohesion process is

where Gcm is the critical energy release rate in the sense of fracture mechanics. The overall behavior of the cohesive zone model is then summarized by

where Yd0m defines the damage threshold, and

F(d) is a monotonically increasing function of the damage variable. From the above, an expression for the damage variable is obtained as

Different definitions for F−1 are available under the

Traction–separation law list. These damage evolution functions are summarized in

Figure 3-44, and the resulting traction–separation laws in

Figure 3-45.

The Linear option specifies a damage evolution function that gives a bilinear traction–separation law as shown in

Figure 3-45.

The Exponential option specifies a more general damage evolution function of the form

where N is a smoothing parameter with a default value equal to 1. The effect of

N on the traction–separation curve can be seen in

Figure 3-45. For the exponential law,

Ydfm is defined as

where Γ() is the gamma function.

A similar damage evolution function is obtained with the Polynomial option. It gives a generalized version of the traction–separation law proposed in

Ref. 160,

The definition of the two variables, Yd0m and

Gcm, requires the introduction of a few concepts related to the mixed mode loading. First, a

mixed mode ratio is introduced

where uI and

uII are the mode I and mode II displacements, respectively. These are obtained from the displacement jump vector

u.

where G0t and

G0s define the damage threshold in tension and shear, respectively.

where Gct and

Gcs are the critical energy release rates for tension and shear, respectively. The variables

α0 and

αc are called the

mode mixity exponents.

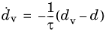

Such deficiencies may be alleviated by introducing some additional form of regularization. Under the Regularization list, it is possible to add the

Delayed damage regularization. This option, available for time-dependent studies, adds a viscous delay to the damage growth. The formulation introduces a viscous damage variable

dv. It redefines

Equation 3-227 so that

(3-233)

where d is the damage variable obtained from any of the available CZM, and

τ is the characteristic time that defines the delay of the decohesion. If the viscous damage is used to stabilize a rate-independent decohesion problem, the value of

τ must be chosen with care. As a rule of thumb,

τ should at least be one or two orders of magnitude smaller than the expected time step. Too large values of

τ can introduce significant amounts of extra fracture energy to the model, and the actual energy dissipated due to damage can exceed the defined critical energy release rates by orders of magnitude.

where Δt is the current time step taken by the time-dependent solver. The value of the viscous damage at the previously converged step,

, is stored as an internal variable.