|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

Click Add.

|

|

4

|

Click

|

|

5

|

|

6

|

Click

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

5

|

|

6

|

In the Function table, enter the following settings:

|

|

7

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

5

|

|

6

|

|

7

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

5

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

5

|

|

6

|

|

7

|

|

8

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

5

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

5

|

|

6

|

|

7

|

|

8

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

5

|

|

6

|

|

7

|

|

8

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

5

|

|

6

|

|

7

|

|

8

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

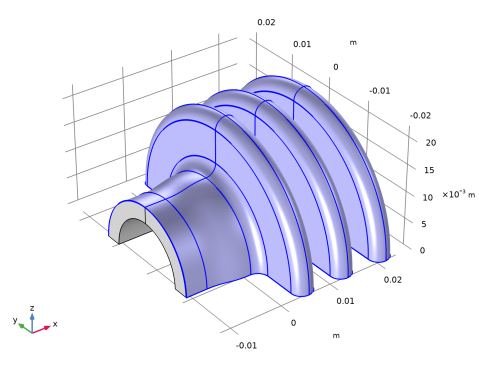

Click in the Graphics window and then press Ctrl+A to select all objects.

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

5

|

|

6

|

|

7

|

|

8

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

5

|

|

6

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

5

|

|

6

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

5

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

Click the Angles button.

|

|

4

|

|

5

|

Locate the Revolution Axis section. Find the Direction of revolution axis subsection. In the xw text field, type 1.

|

|

6

|

|

7

|

|

8

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

5

|

|

6

|

|

7

|

Click OK.

|

|

8

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

5

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

1

|

In the Model Builder window, under Component 1 (comp1)>Heat Transfer in Solids (ht) click Initial Values 1.

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

1

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

5

|

|

6

|

|

7

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

5

|

|

6

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

1

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

Click OK.

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

Use the Graphics toolbox to get a satisfying view.

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

Click Yes to confirm.

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

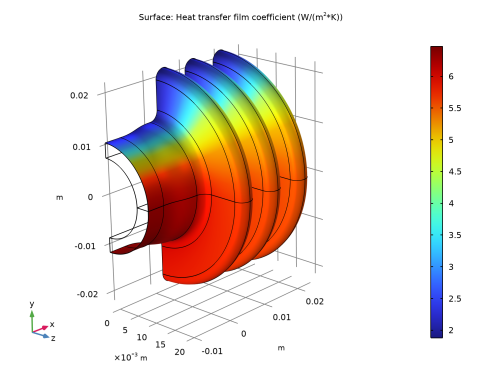

In the Settings window for 3D Plot Group, type Heat Transfer Film Coefficient in the Label text field.

|

|

3

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

In the Settings window for Surface, click Replace Expression in the upper-right corner of the Expression section. From the menu, choose Component 1 (comp1)>Definitions>Variables>Hc - Heat transfer film coefficient - W/(m²·K).

|

|

3

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

Click Replace Expression in the upper-right corner of the Expressions section. From the menu, choose Component 1 (comp1)>Heat Transfer in Solids>Boundary fluxes>ht.ntflux - Normal total heat flux - W/m².

|

|

5

|

Click

|

|

1

|

Go to the Table window.

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

5

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|

|

5

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

Click

|

|

5

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

Click Yes to confirm.

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

In the Settings window for Global, click Add Expression in the upper-right corner of the y-Axis Data section. From the menu, choose Component 1 (comp1)>Definitions>Variables>P_cooling - Cooling power - W.

|

|

3

|

|

1

|

|

2

|

|

3

|

|

4

|